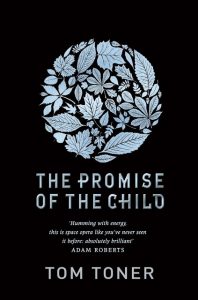

So what is The Promise of the Child about? It’s certainly created a buzz, with lots of rumblings above the usual created by the publicity machine that this is the debut of something and someone extraordinary.

So what is The Promise of the Child about? It’s certainly created a buzz, with lots of rumblings above the usual created by the publicity machine that this is the debut of something and someone extraordinary.

Well, it’s a Space Opera. Nothing particularly new there, you might think. Peter F Hamilton, Neal Asher, Iain M Banks – there’s a fair bit of it about.

So, what makes this one get the reaction it has? It is, at first, a tad daunting, as this is one that hits the ground running, in a blur of different perspectives. Think Steven Erikson’s The Shadow of the Moon, but as a Space Opera. Behind the initial flash and bang, the plot is actually fairly standard fare, though there are some welcome aspects that bring something new to the table. Generally, as the book progresses, there’s a sense of expanding scale, reminiscent to me of a Jack Vance novel. Places, planets and people are all dropped into the narrative in such a way that their cumulative effect gives the impression of being part of a much bigger picture than that told here. However, the disjointed nature of the initial parts may cause some readers to lose track. It is one you’ve got to follow carefully and to some extent connect the dots yourself.

Part I of the novel is a rather fragmented amalgam of the different places and characters that we will get to know more of in the progress of the plot. There’s the reluctant hero, Lycaste, who initially tries to live a quiet and secluded life. There’s also big nasty space warriors that seems to have been propelled from the pages of a Warhammer 40 000 novel, master political schemers, and a pretender to the throne. Threen Corphuso Trohilat is the magician of our story, an architect and owner of the Shell, an ultimate weapon capable of mass destruction that has been captured (with Corphuso) and is being transported by the Prism.

Part II mainly tells of Lycaste and his secluded lifestyle. Wanting little else but to be left alone with his books and his model palace that he is building, his life is changed with the arrival of Callistemon, Plenipotentiary of the Greater Second, taking a census of the outlying provinces. Lycaste finds himself so at odds with Callistemon that, after an unfortunate accident, Lycaste has to leave and begin his bildungsroman journey.

“How little is the promise of the child fulfilled in the man.”

Whilst it has many of the usual trappings of Space Opera, the focus of the novel is not on a Neal Asher epic scale, of big weapons and bigger spaceships. Instead this is more of an Ursula K le Guin or an Anne McCaffrey novel, like Joan Vinge’s The Snow Queen or CJ Cherryh’s Cyteen tales, with more of a focus on characterisation and societal mores than action and weaponry. Though there are battles on land, in the air and in space, much of the novel is character-based rather than weaponry-centred. The characterisation is of a sort that raises the game.

The central premise is that this is a universe set in our far future. Whilst Earth is still present in the story (as the Old World) the human race has expanded and transformed into a multitude of different sub-species.

As befitting such a sprawling vista, there’s a sense of both decay and opulence here which reminded me of Asimov’s Foundation or Vance’s Dying Earth. We see an Empire that is past its prime, that may be rather stretched or even outlived its effectiveness. The provinces are rather bucolic but backward – Lycaste is impressed by the present of a simple telescope, for example – whilst in the Galactic Centre we have mega-weapons and other things of mass destruction elevated to an almost mystical state.

In terms of the big ideas that no self-respecting SF novel should be without, there’s science-magic, in a universe that suits Arthur C Clarke’s old maxim, “Any science indistinguishable from magic….” There’s Galactic Empires, Kings and princesses and a certain degree of Iain M Banks’s bloody big spaceships known as Voidships. We’ve even got elf-like aliens in the form of the Lacaille.

It all sounds like a pick and mix mess – and at times things can seem a little unclear. And yet, surprisingly, in the end it works.

After the initial perplexing introduction we slowly discover that this is a distant future where the Amaranthine Firmament – evolved humans – have split into many different species. We spend much of the book meeting these in a decaying Empire scenario, where races such as the over-sized Melius, the Vulgar, the Zelioceti and the immortal Ameranthine of the Firmament are seemingly at war with another group of rather bizarre creatures collectively referred to as ‘the Prism’, a loosely collected amalgam of eleven hominid races populating more than a thousand individual kingdom states.

The Prism are currently winning, albeit around the edges of the Fermament, whilst the immortal Amaranthine are embroiled in a new claim to the throne from Pretender Aaron the Long-Life (whose name, bizarrely, kept me thinking of milk). The current holder, Sabran, is old and decrepit, and to the consternation of his retinue is backing Aaron’s claim, wishing to crown him Emperor and award his prophet Maneker the title of Vice Regent and the Solar Satrapy of Gliese. Some of our characters are naturally involved in all of this and due to become much more prominent that they are initially.

As events unfold, and war rages across the planets, it is not entirely clear what’s happening at all times, though Aaron seems to be manipulating our collective towards some important event. Lycaste is clearly part of this master-plan, though he is unknowing of it or its purpose. And then there’s the Shell, which is clearly being set up to do something.

It is Part IV that brings it all together, although there are issues that are clearly meant to be resolved in the other books of this proposed-trilogy. Whilst some may be irritated at the many different perspectives that are jumped to and from, the book is able to bring many elements together at the end. Indeed, there’s much to admire here at how this is done, even if I couldn’t quite shake the feeling that the book wasn’t so full of its own self-satisfaction. It can come across as a little smug.

Nevertheless, I quibble. In a year of quite surprising debuts, not all of them good, this has been one of the more pleasant revelations. The Promise of the Child is a rip-roaring, full-blown Space Opera, with Epic-ness writ large across its pages, and one that will repay rereading. Remember the impact Hannu Rajaniemi made with his debut, The Quantum Thief? I think that this one will have a similar effect.

The Problem of the Child is a grand debut that fuses the traditions of older SF with an intelligent, literary tone and an anthropological perspective. It may not be quite as unique as what the publicity is saying, but it is still an ambitious first novel and suggests that we have much more to hear from this promising young writer. As they say in 1960’s parlance, “Prepare to get your mind blown.” Dare I say it? – The Promise of the Child is a book with ‘promise’, that may create a standard for other new SF writers to meet.

Despite some slight issues, this is an impressive debut and one of my favourite books of the year, I think.

The Promise of the Child by Tom Toner

Volume One of the Ameranthine Spectrum

Published by Gollancz, November 2015

544 pages

ISBN: 978-1473211360

Review by Mark Yon