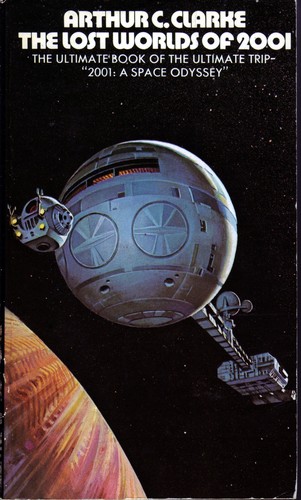

So, this was a re-read. I picked this up because it happens to be 50 years this week (as I type) since the US release of the MGM movie 2001: A Space Odyssey. For the record, and as regular SFFWorld readers may know, I’m a Clarke fan. This book was one of my Dad’s old paperbacks, which I read after reading the novel of 2001, looking for answers and trying to work out what the movie was about. The iconic cover to the NEL paperback* (see right) seemed to suggest that this book might help.

So, this was a re-read. I picked this up because it happens to be 50 years this week (as I type) since the US release of the MGM movie 2001: A Space Odyssey. For the record, and as regular SFFWorld readers may know, I’m a Clarke fan. This book was one of my Dad’s old paperbacks, which I read after reading the novel of 2001, looking for answers and trying to work out what the movie was about. The iconic cover to the NEL paperback* (see right) seemed to suggest that this book might help.

Just to put that into perspective, my discovery of the book would have been in the mid-to-late 1970’s, before the arrival of VHS and Betamax video recorders, but long after the movie had gone from the cinema. (My first watch, if I remember right, was a showing one Christmas on BBC television.) I had read just about every Clarke novel I could get my hands on – at this time it was up to Imperial Earth (1975) which I read in about 1978, I think. (It took a little while to appear in my small-town local library.)

Although these days, with the advent of Blu-ray, a big television screen and a surround sound setup, I have seen the movie many times – often once a year – this is the first time in over twenty years since I’ve read this book other than to dip in and out for the odd reference. If you’re a fan of the movie (and I know there’s a lot of people who are not!) it’s a rewarding read.

First of all – make sure you’ve seen the movie and/or read the novel before this book.

Sir Arthur is at pains to point out that his book 2001: A Space Odyssey is not a “novelisation” of the script, but instead something that was written at the same time as the development of the screenplay.

“In theory, therefore, the novel would be written (with an eye on the screen) and the script would be derived from this. In practice, the result was far more complex; toward the end, both novel and screenplay were being written simultaneously, with feedback in both directions. Some parts of the novel had their final revisions after we had seen the rushes based on the screenplay based on earlier versions of the novel . . . and so on.”

In fact, reading this book shows you how close Sir Arthur and Stanley Kubrick worked together before the movie was made – a film that was planned to write and make in two years but, in the end, took four. Clarke here gives some brief extracts of the log/diary that he kept whilst this collaboration was taking place, which are brief but typically Clarke.

“June 20. Finished the opening chapter, “View from the Year 2000,” and started on the robot sequence.

July 1. Last day working at Time/Life completing Man and Space. Checked into new suite, 1008, at the Hotel Chelsea.

July 2-8. Averaging one or two thousand words a day. Stanley reads first five chapters and says “We’ve got a best seller here.”

July 9. Spent much of afternoon teaching Stanley how to use the slide rule – he’s fascinated.”

The novel 2001 gives more idea of that ending, which Kubrick kept deliberately oblique in the movie, but this book explains further what Kubrick & Clarke’s ambitious intentions were.

What is fascinating here is that Lost Worlds shows the reader how a movie is made, and, most interestingly, the roads not taken in that process.

The book begins with View from the Year 2000, a short extrapolated history of an imaginary Space Race, extending past the Moon landings (this was written in 1964) to Mars and beyond. Wonderfully optimistic, the prologue tells of rock-like life discovered on Mars and the mysterious outer planets of Saturn and Jupiter, leading to the stars and beyond. This is typical Clarke-style fiction that wouldn’t be out of place in one of his novels.

The original Clarke story, The Sentinel (1948), the origin of (and inspiration for) the monolith story, is also included in this book. There are clear links between the two.

Obviously, in any production, there are ideas that are considered but then rejected. Lost Worlds is full of these, which suggest that the final movie could have been very different from what we actually saw. There are lots of little “Wow” moments throughout the book. I don’t want to give them all, but here’s a few ideas that stuck with me from the early stages of writing that were thought of and then (in most cases, thankfully) rejected:

- The discovery of the alien monolith/artifact TMA-1 was, like The Sentinel, meant to be the ending of the film/book but was quickly seen as a start, rather than a conclusion.

- Kubrick wanted to have the movie called “Journey Beyond the Stars”, which Sir Arthur hated. Other titles considered were Universe, Tunnel to the Stars, and Planetfall. It was not until April 1965 that Stanley selected 2001: A Space Odyssey, entirely his idea, to which Clarke agreed.

- Sir Arthur suggested to Kubrick that the aliens might be machines who regard organic life as a hideous disease.

- Clarke also proposed in the early stages that the people we meet on the other star system are humans who were collected from Earth a hundred thousand years ago, and hence are virtually identical with us.

- Kubrick wanted to include the idea from Clarke’s Childhood’s End that the aliens looked like devils.

- The first version of the famous monolith was the largest block of lucite produced in the world up to that date, weighing three tons. (It was rejected when it didn’t look right.)

- Originally the monolith was to be a transparent cube or a tetrahedon.

- The novel was meant to come out before the movie. Clarke felt that it was about finished in April 1966, but Kubrick wanted to work on it more. It was further revised by Clarke (on Kubrick’s suggestions) continuously until its eventual release, months after the movie in the summer of 1968.

Whilst still revising the novel/script, Clarke went to the movie set a few times, but was not always a revered visitor:

“November 10. Accompanied Stan and the design staff into the Earth-orbit ship and happened to remark that the cockpit looked like a Chinese restaurant. Stan said that killed it instantly for him and called for revisions. Must keep away from the Art Department for a few days.”

It is at this point that we get to the core of this book. The remainder of this book are early versions of the novel used to develop a script, begun as part of the Clarke-Kubrick collaboration in progress and put together as an incomplete, alternative version of the 2001 plot. They are discarded elements excised or totally different from the final film version. All are intriguing.

And here was my surprise. This alternate tale is much more typically Clarke in terms of style, something not dissimilar from, say, Rendezvous with Rama or even Prelude to Space. These look more at many of the issues subtly referenced in the movie – the future relationship between Man and robots, HAL and Artificial Intelligence, Asimov’s Laws of Robotics, the exploration of Mars, Clarke’s ever-abiding interest in the ocean, the cosmic grandeur of the universe.

Most interestingly, there are characters fleshed out which are barely mentioned by name in the movie, not just Dave Bowman and Frank (here Kelvin) Poole, but also their other colleagues on the Discovery (Kaminski, Kimball, Hunter, and Whitehead.) Not only that, but there’s typically Clarkean big cosmic moments, a more Childhood’s End-type ending through the Star Gate, and even a named alien guiding Mankind’s future destiny. In this alternate world HAL is Athena, and in the early parts of the book is a mobile robot named Socrates – how different in the movie that would have been! Traveling from Mars to Venus and even under the oceans, this version of 2001 is a fuller and less clinical version of the 2001 novel and the original movie.

As engaging as this was, this actually may also be the book’s downfall. It is also more straight-forward and less ambiguous than the movie version, which may be why it wasn’t the basis for the final script. One of the reasons that I feel that the movie has a timeless quality is the fact that the elements that would have dated it have not been included. Instead, the dialogue is kept deliberately brief and general, the characterisation to a minimum (it has been noted by some critics that often the most interesting character is HAL the computer) and therefore the details more ambiguous. Even now, fifty years on, discussion over what the movie is about is still common. The film makes people think and wonder and watch again. Whilst this version of the story is great, it is also quite traditional. It would make a great movie – but not one that would be as revered as 2001 is, in fifty years’ time.

Reading Lost Worlds in 2018 I was surprised by how much of the original book/film I had forgotten but also how much I enjoyed this alternate, if more talky, version. Clarke’s writing voice is as clear as ever, with that sense of humour and deprecation not expected from someone nicknamed ‘The Ego’. A Director’s Cut edition of the novel, combining elements of this with the main plot of the movie, would have been brilliant.

Looking back, although I enjoyed this when I first read it, I remember this as an inconsequential book, feeling that it was full of incomplete bits of wastage from the years spent by Clarke on outlining the plot for Kubrick and cobbled together by a publisher eager to cash in on the 2001 phenomenon.

I was wrong.

With the advantage of hindsight and a greater knowledge of the movie and Clarke’s work, I find that Lost Worlds is a deeper and richer experience than I remembered. For too long this book has been left on my shelf – it is a worthy read, and one which I would’ve loved to see published as an alternate universe Clarke novel.

As we celebrate the 50th anniversary of the movie’s release, this is an appropriate read to show what else could have been achieved with the material. This was a surprisingly good read and one worth getting hold of if you can.

The Lost Worlds of 2001 by Arthur C Clarke

First published by Sidgwick & Jackson, 1972

240 pages

ISBN: 9780283979040

Review by Mark Yon

*From the great artist Bruce Pennington, one of the iconic artists of the UK in the 1970’s: http://www.brucepennington.co.uk